“The best executive is the one who has sense enough to pick good men to do what he wants done, and self-restraint enough to keep from meddling with them while they do it.” – Theodore Roosevelt

Did you know that academic research consistently defines laissez-faire leadership not as a relaxed style, but as a state of “non-leadership” or “zero leadership”—a corrosive failure that is positively correlated with workplace stress, role conflict, and even bullying? In an era where employee autonomy is championed as a key driver of innovation and engagement, it has become dangerously easy to confuse strategic empowerment with passive neglect. This exploration will draw a sharp, evidence-based line between these two profoundly different phenomena, providing a definitive framework for understanding the critical difference between a leader who develops talent and one who simply disappears.

The Principle

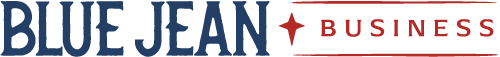

The core principle is that strategic delegation and laissez-faire leadership are not different points on a continuum of “hands-off” management, but are fundamentally different in their intent, process, and accountability. Healthy delegation is an active, intentional, and highly engaged leadership competency. It is a structured process involving the deliberate transfer of both responsibility for a task and the authority required to execute it. The leader’s role shifts from director to architect—designing the conditions for success by carefully selecting the right person, providing crystal-clear objectives, ensuring access to necessary resources, and establishing a robust framework of communication and support. The ultimate goal of delegation is not merely to offload work, but to build organizational capacity, accelerate results, and systematically develop the skills and confidence of team members. It is an investment in human capital that communicates trust and a commitment to growth.

In stark contrast, laissez-faire leadership is the abdication of responsibility—a leadership vacuum defined by what the leader consistently fails to do. Originating from the French phrase “to let it do,” this style is characterized in contemporary leadership models as a passive and destructive behavior to be avoided. A laissez-faire leader is consistently absent when needed, avoids making decisions, and provides no meaningful feedback, guidance, or support. This inaction is not a strategic choice to empower a capable employee; rather, it often stems from the leader’s own indecisiveness, disinterest, or desire to evade the core duties of their role. While both approaches may result in an employee working autonomously, delegation is a carefully constructed act of empowerment, while laissez-faire is a destructive act of abandonment.

Why This Principle Matters

Understanding and mastering this principle is of paramount importance for leadership development, personal growth, and the overall health of any organization. For business owners and senior executives, effective delegation is the primary mechanism for achieving scale. A leader who cannot or will not delegate becomes a bottleneck, limiting the organization’s growth to the scope of their own personal capacity. By strategically entrusting others with ownership, leaders free up their own invaluable time and cognitive resources to focus on the high-leverage activities that only they can perform: setting long-term vision, formulating strategy, cultivating critical stakeholder relationships, and navigating the competitive landscape. Without this, a leader remains perpetually trapped in the operational weeds, unable to steer the ship because they are too busy rowing.

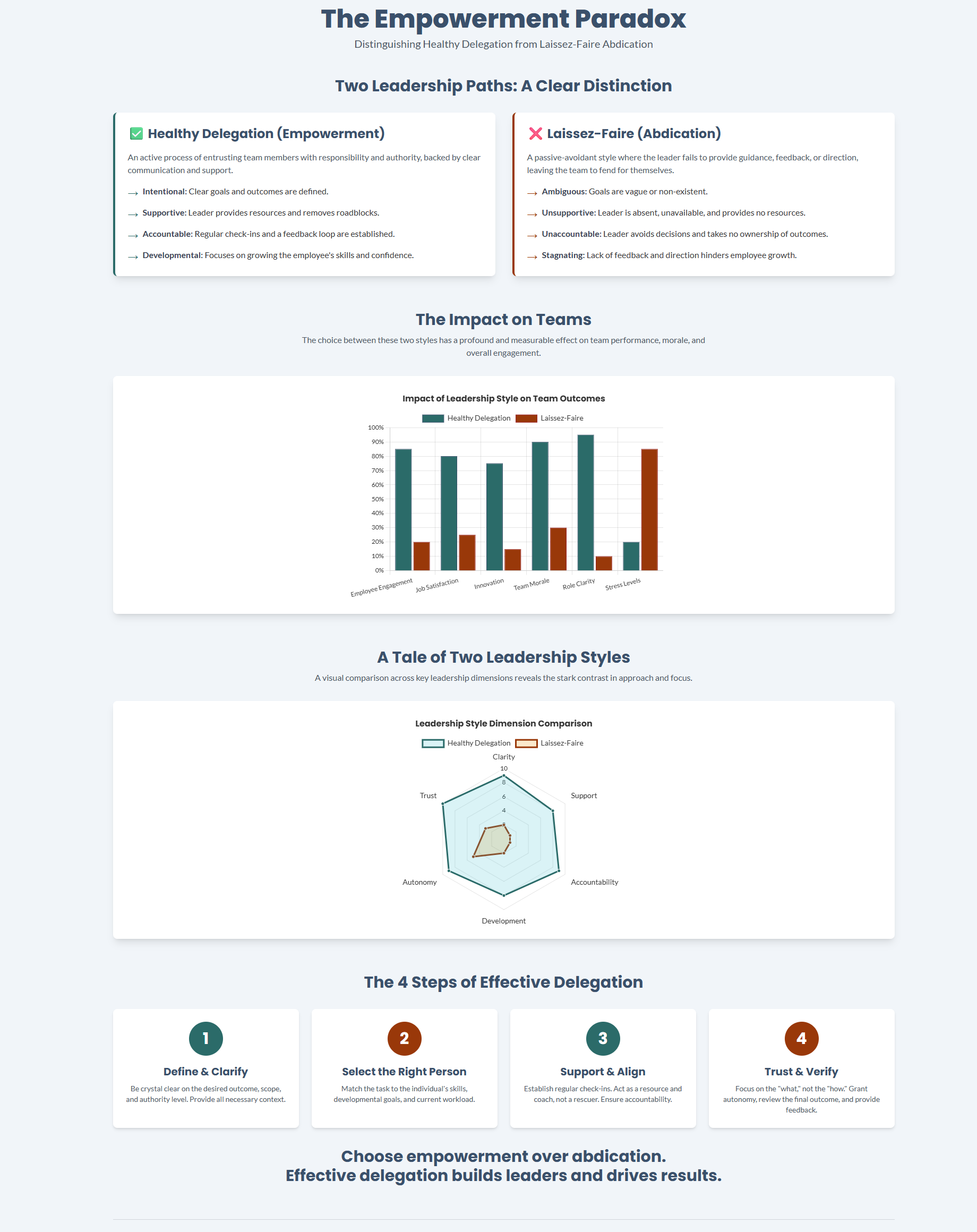

The consequences of failing to distinguish between these two concepts are severe and far-reaching. A culture of strategic delegation is a powerful engine for human capital development. It signals profound trust in employees’ abilities, which is a critical driver of job satisfaction, engagement, and loyalty. It provides invaluable, real-world learning experiences that stretch capabilities, build new skills, and foster a deep sense of psychological ownership. This process creates a resilient and adaptable organization with a robust pipeline of internal talent ready to assume greater responsibility.

Conversely, a laissez-faire environment is toxic to both individuals and the organization. Far from being liberating, the absence of leadership is a potent workplace stressor, consistently linked in research to heightened role ambiguity, interpersonal conflict, and an increased exposure to workplace bullying. When employees are left without clear direction, feedback, or support, their motivation is extinguished through a process of behavioral extinction—good work goes unrecognized, and thus, the incentive to perform well vanishes. This leads to a cascade of negative outcomes: diminished morale, lower productivity, and a culture of blame-shifting where no one takes ownership because the support structure is non-existent. At the organizational level, this translates to missed opportunities, poor quality control, and an inability to respond effectively to crises, ultimately eroding the company’s performance and competitive standing.

Why this Principle Works

The dramatic difference in outcomes between delegation and laissez-faire leadership is explained by foundational academic theories of leadership and motivation. The Hersey-Blanchard Situational Leadership Theory provides a robust framework for understanding why and when granting autonomy is appropriate. The model’s core tenet is that there is no single best leadership style; effectiveness is contingent upon the “development level” of the follower, which is a combination of their competence (skill and knowledge) and commitment (confidence and motivation) for a specific task. The model outlines four distinct leadership styles a leader must adapt to the situation:

- S1: Directing/Telling: High task, low relationship. For followers with low competence but high commitment (e.g., an enthusiastic new hire). The leader provides specific instructions and supervises closely.

- S2: Coaching/Selling: High task, high relationship. For followers with some competence but low commitment (e.g., a team member who has become discouraged). The leader provides direction but also support and two-way communication to build buy-in.

- S3: Supporting/Participating: Low task, high relationship. For followers with high competence but variable commitment. The leader facilitates and supports, but the follower has the skills to do the job.

- S4: Delegating: Low task, low relationship. This style is appropriate only for followers who are highly competent and highly committed. The leader can turn over responsibility for decisions and implementation because the follower has earned that autonomy.

Within this model, healthy delegation is the skillful and correct application of the S4 style to a follower who is ready for it. The leader’s choice to be “hands-off” is a strategic diagnosis. Laissez-faire leadership, in contrast, is revealed as leadership malpractice: the indiscriminate and inappropriate application of an S4-like style to followers who are not ready. Applying a delegating style to a D1 employee who needs clear direction or a D2 employee who needs coaching is negligent. It sets the employee up for failure and creates the exact conditions of stress, role ambiguity, and poor performance documented in laissez-faire research. The model thus proves that delegation is a skillful, adaptive behavior, while laissez-faire is a fundamental failure to perform the diagnostic work required of a leader.

How this Principle Works

The management philosophy of Warren Buffett at Berkshire Hathaway is frequently mislabeled as “laissez-faire” but serves as a masterclass in strategic, high-level delegation. His success is not built on passive absence but on an intensely active and intentional process of empowerment. First, his process is predicated on meticulous selection. His famous mantra, “Hire well, manage little,” highlights that his ability to be hands-off is the result of an extremely hands-on process of identifying subsidiary CEOs with unimpeachable integrity, intelligence, and a passion for their business. This is the critical first step of effective delegation. Second, he provides clear principles, not restrictive rules. Instead of a thick operational manual, Buffett provides his managers with a set of core values and “principles of behavior” that establish clear ethical and cultural guardrails. This ensures strategic alignment without resorting to micromanagement. Third, he grants extreme trust and autonomy. Once the right leaders are in place and the principles are clear, Buffett gives them complete operational freedom to run their businesses as they see fit. This is a deliberate transfer of authority rooted in his confidence in their expertise, fostering a powerful culture of ownership. Finally, and most critically, he retains ultimate accountability. Buffett is the ultimate steward of shareholder capital. His famous annual letters are models of transparency and deep engagement with business results, demonstrating that while he does not manage day-to-day operations, he is intensely focused on outcomes and holds himself accountable for the company’s overall performance. His success is the product of being intensely “hands-on” in the most crucial upstream leadership activities: selecting talent, allocating capital, and setting the vision. This is the hallmark of effective delegation, not an abdication of leadership.

Practical Strategies for leaders

To ensure you are delegating effectively and not lapsing into laissez-faire neglect, focus on integrating these actionable behaviors and structured processes into your leadership practice. These strategies operationalize the core principles of intent, process, and accountability.

1. Define the “What” and “Why,” Not Just the “How.”

- Clarify the Desired Outcome: Before delegating, you must have a crystal-clear vision of what success looks like. Define the final deliverable using specific, measurable, agreed-upon, realistic, and time-bound (SMART) goals. A vague assignment like “handle the marketing report” is a hallmark of laissez-faire leadership; a clear directive like “produce a 10-page analysis of Q3 marketing performance, focusing on lead conversion rates, to be presented at the October 15th leadership meeting” is the foundation of effective delegation.

- Explain the Strategic Context: People are more motivated when they understand the purpose behind their work. Explain how the delegated task fits into the larger team and organizational goals. This context empowers them to make better independent decisions that align with the bigger picture.

- Establish Clear Authority and Boundaries: Explicitly define the employee’s scope of authority. Let them know what decisions they can make on their own, which ones require consultation, and which ones remain with you. This prevents hesitation and ensures they feel empowered to act within the defined guardrails.

2. Select the Right Person for the Right Reason.

- Assess Competence and Commitment: Delegation is not a one-size-fits-all action. Evaluate the team member’s skills, experience, and motivation in relation to the specific task. A complex, strategic project is best suited for a seasoned, self-directed employee, while a more straightforward task can be a developmental opportunity for a junior team member.

- Delegate for Development, Not Just Dumping: The most effective leaders view delegation as a primary tool for employee growth. Look for opportunities to assign tasks that will stretch an employee’s skills and build their confidence. Avoid the trap of only delegating undesirable or mundane tasks, as this will be perceived as simply offloading your unwanted work.

- Communicate Your Trust: When you assign the task, explicitly state why you chose them. A simple statement like, “I’m giving this to you because I was impressed with your analytical work on the last project and I believe you’re ready to take the lead on this,” can transform the assignment from a burden into a vote of confidence.

3. Create a Robust System of Support and Accountability.

- Schedule Proactive Check-ins: Delegation is not a “fire and forget” mission. Establish a regular cadence for check-ins (e.g., a 15-minute sync every Tuesday). The purpose of these meetings is not to micromanage, but to monitor progress against goals, offer strategic guidance, and proactively help remove any obstacles they are facing. A laissez-faire leader is absent; an effective delegator is available and engaged.

- Act as a Coach, Not a Problem-Solver: When an employee encounters a challenge, resist the urge to immediately provide the solution. Instead, adopt a coaching stance. Ask questions that build their critical thinking and problem-solving skills, such as: “What options have you considered?” “What are the pros and cons of each approach?” “What do you recommend we do?”. This builds their self-reliance for future challenges.

- Retain Ultimate Accountability: This is a non-negotiable principle. While the employee is responsible for executing the task, you, as the leader, remain ultimately accountable for the outcome. When a mistake happens, approach it as a learning opportunity for the process, not a personal failure of the employee. Publicly own the team’s setbacks just as you celebrate their successes. This creates the psychological safety necessary for employees to take risks and innovate.

Critical Reflection

- When I last delegated a significant task, was my primary motivation to develop my team member’s skills and leverage their talent, or was it to quickly get an undesirable item off my to-do list?

- Consider the communication patterns after I delegate. Do I proactively initiate scheduled check-ins to offer support and ensure alignment, or do I typically wait for the employee to contact me, often only when a problem has arisen?

- Think of the last time a delegated project failed to meet expectations. Did I take ownership of the failure and lead a blameless analysis of the process to identify learning opportunities, or did I hold the employee solely accountable for the negative outcome?

- Do my team members feel genuinely empowered to make decisions within their scope of authority, or do they frequently seek my approval for minor issues, suggesting a lack of clarity or trust?

- If a crisis were to erupt today on a project I have delegated, would my team describe my involvement as decisive, supportive, and present, or as absent, indecisive, and uncontactable?

How to Begin Applying the Principle

The “Strategic Offload” 30-Day Experiment

Week 1: Identify & Document. Carve out 30 minutes this week. Brainstorm a list of all your recurring tasks and responsibilities. Categorize them into two columns: “Only I Can Do This” (e.g., final budget approval, strategic planning) and “Someone Else Could Do This” (e.g., drafting the weekly report, managing a vendor relationship, running the monthly project review meeting). Choose one high-value item from the second column that would be a good developmental opportunity for a team member.

Week 2: Delegate with Clarity. Schedule a one-on-one meeting with the person you’ve selected. Use the “Practical Strategies” above as a checklist. Frame the task as a growth opportunity. Explicitly define the desired outcome, the level of authority they have, the resources available, and the schedule for your check-ins. At the end of the meeting, ask them to summarize their understanding to ensure perfect alignment.

Week 3: Coach and Support. During this week, your primary role is to honor the framework you’ve established. Let them do the work. If they come to you with a problem, use coaching questions to guide them. If others try to pull you in, redirect them to the new owner. Your job is to be an available resource, not an active participant.

Week 4: Review and Calibrate. At the end of the month, conduct a review of the delegated task. Provide constructive feedback on what went well and what could be improved. More importantly, ask for their feedback on the process: “Did you feel you had enough clarity and support from me?” “What could I have done differently to help you succeed?” Use this feedback to refine your delegation process for the next task you strategically offload.

Wrap up

The distinction between strategic delegation and laissez-faire leadership is not a subtle nuance of management theory; it is the fundamental difference between building a scalable, high-performing organization and presiding over its stagnation. Delegation is an active, disciplined, and intentional process of empowerment. It acts as a force multiplier for your leadership impact, a powerful engine for developing your people, and the single most effective tool for scaling your organization’s capacity. Abdication, cloaked in the guise of “trust,” is a passive neglect that creates chaos, erodes morale, crushes innovation, and ultimately guarantees failure. For the modern leader navigating a complex and fast-moving world, mastering the art and science of strategic delegation is not optional; it is the very essence of effective leadership.

Next Steps

- Book: Multipliers: How the Best Leaders Make Everyone Smarter by Liz Wiseman. A brilliant exploration of how certain leaders amplify the intelligence and capabilities of their teams, with delegation as a core theme.

- Article: “Management Time: Who’s Got the Monkey?“ by William Oncken, Jr., and Donald L. Wass (Harvard Business Review, 1974). This is the seminal, must-read article on ownership, responsibility, and how not to let your subordinates’ problems become your own.

- Book: Leadership and the One Minute Manager by Ken Blanchard, Patricia Zigarmi, and Drea Zigarmi. This book provides a practical and accessible guide to implementing the Situational Leadership model, helping you diagnose follower readiness and apply the correct leadership style.